Drawn by Nature: Transform urban yards into wildlife habitats

An urban yard can become a richly layered ecosystem.

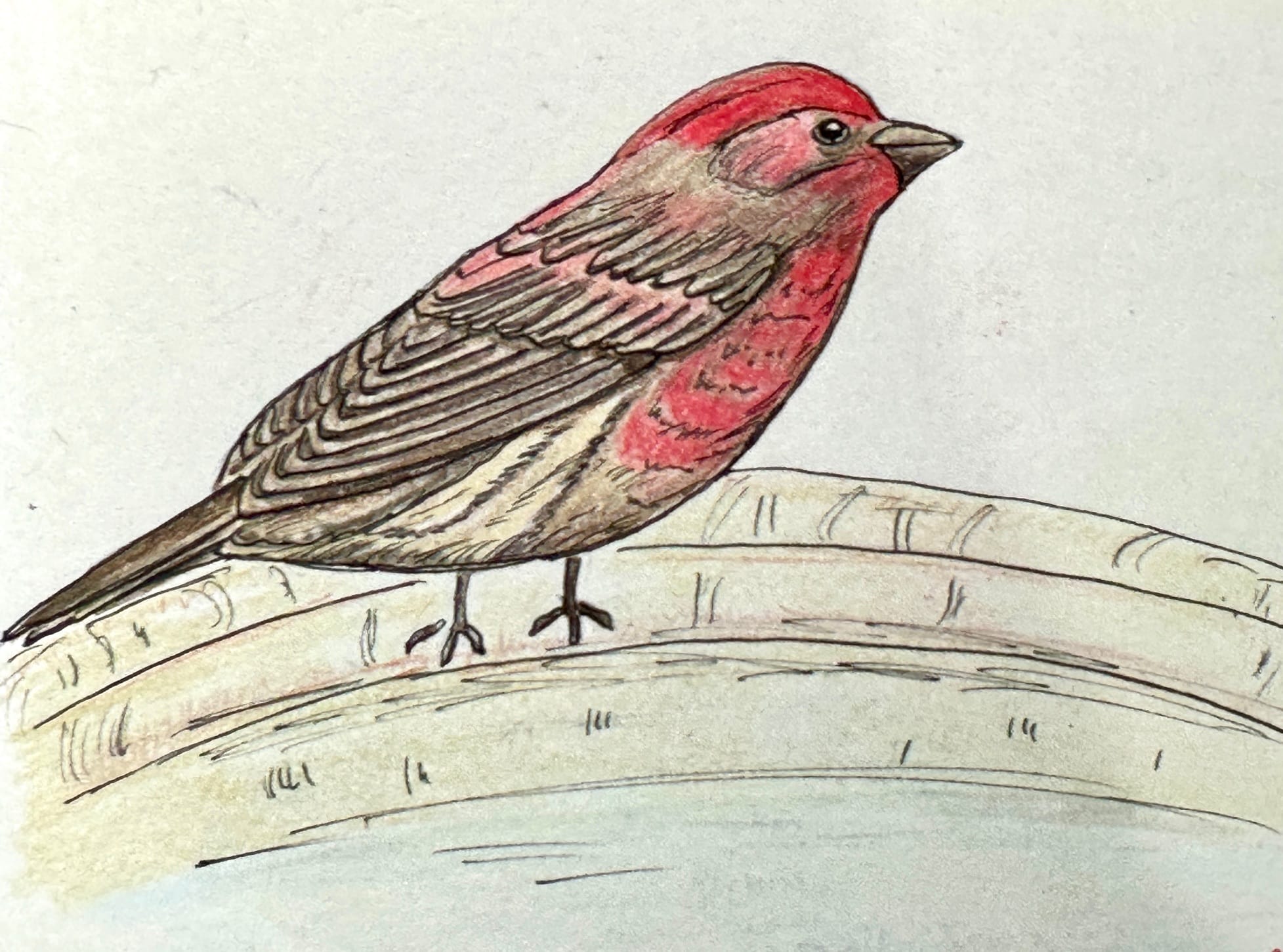

Berries light up like rubies when sunlight hits our backyard currant bushes.

We planted them years ago with the intention to make jelly or baked goods with these relatives of gooseberries, but I’ve found as much pleasure watching young bluebirds attacking them like teens on Takis.

It’s one of many ways birds and animals can find food or shelter in our yard, even though we live in the city of St. Cloud. It’s not a rural woodland like where I grew up, but there are many ways to support a variety of wildlife.

Sign up for Project Optimist's newsletter

Solution-focused news, local art, community conversations

It's free. No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Like a growing number of homeowners, we know that even an urban yard can be a richly layered ecosystem. It can be a small change, like adding a birdbath or planting a pollinator garden, or it can be a bigger undertaking.

The National Wildlife Federation offers checklists and a formal program for anyone interested in creating a Certified Wildlife Habitat® at home or at a school, church, or business.

There also are plenty of Minnesota programs that support similar efforts. The Lawns to Legumes program through the Minnesota Board of Soil and Water Resources offers grants, coaching, and resources for turning grass lawns into pollinator habitats.

Here are some of the best practices you can try at home, from small projects to larger efforts, that support seasonal and year-round wildlife, along with migrating species who are just passing through.

Trees and shrubs

Plant native trees that will shade your residence, soak up excessive rains, and provide food and shelter for wildlife. Look for hardwoods such as oak, maples, basswood, and birch. Spruce, white, and red pines, and fir trees also provide food and shelter, especially in the winter when deciduous trees lose their leaves. Keep tree saplings well-watered while they are getting established.

Native shrubs also offer nesting sites, shelter, and food for wildlife. Look for natives such as highbush cranberry, blueberry, currants, serviceberry (Juneberry), black chokeberry, and redosier dogwood.

Native pollinator plants

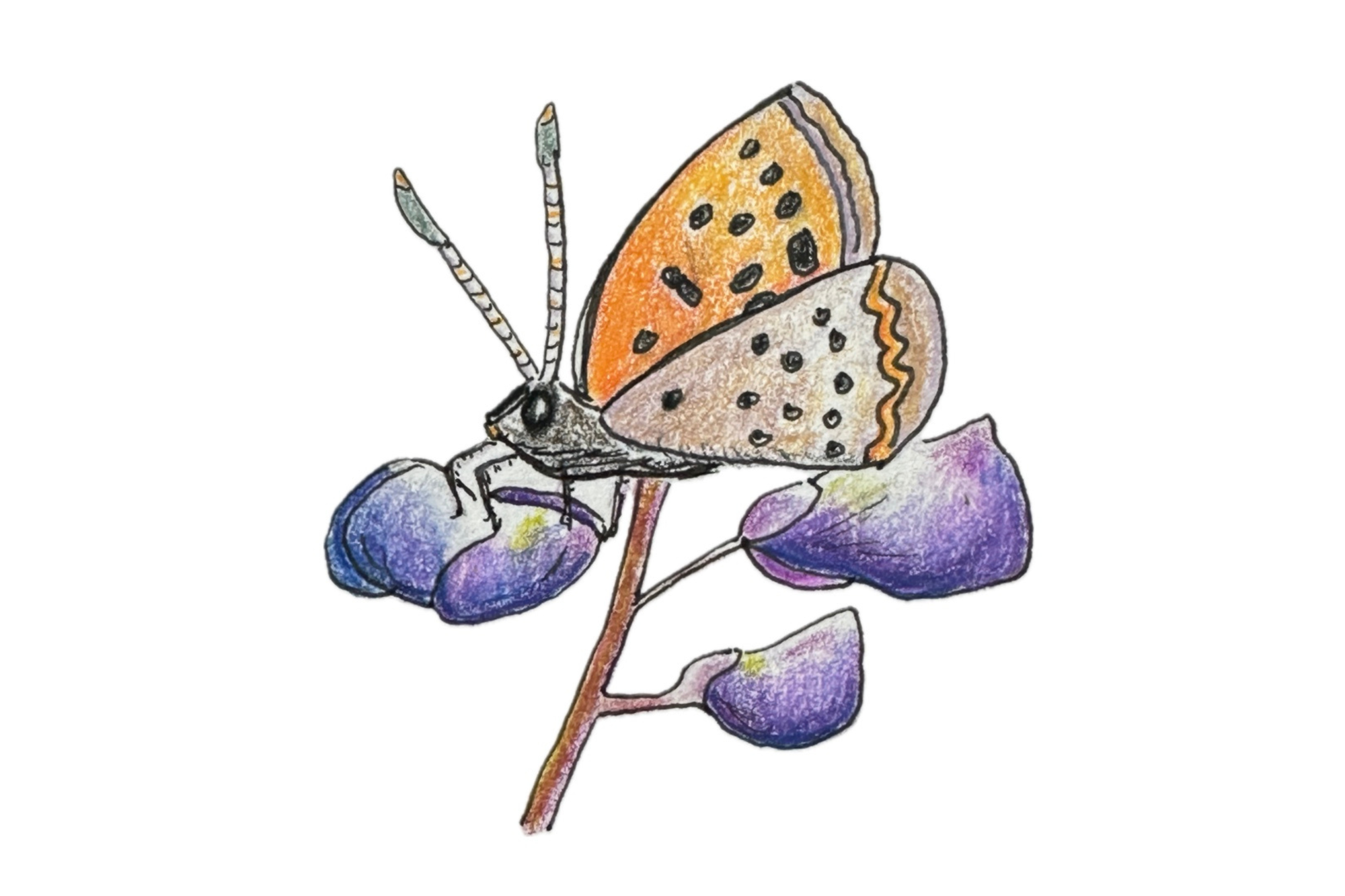

Support bees, butterflies, and other pollinators, such as hummingbirds, by creating a native garden that includes plants such as false indigo, hyssop, bee balm, butterfly weed, milkweed, asters, and native grasses. Native plants often can handle extremes of climate change, not requiring as much watering and are able to better absorb excess rain.

Leave some leaf and brush debris

While most homeowners rush to clean up fallen leaves each autumn, choose a lesser-used corner of the yard and leave a few inches of leaves behind. These shelter hibernating frogs and toads, salamanders, chipmunks, bees, and cocoons for non-migrating butterflies. A small brush pile or a few logs or rocks that can provide shelter also benefit wildlife.

If a dead tree or branch isn’t in danger of falling and causing damage, it can shelter birds, squirrels, raccoons, bats, and more; it can also provide a lookout, and a food source as the decaying wood attracts insects, fungi, mosses, and lichen.

Project OptimistLisa McClintick

Project OptimistLisa McClintick

Water sources

A bird bath, puddling dish, waterfall, rain garden, or permanent pond can provide a vital resource to wildlife as a constant, dependable water source and a place for birds to bathe.

Supplemental shelters

Bee houses, which provide native bees safe places to lay eggs, are easy to make and replicate hollow stems of native plants. Creating a shaded shelter for insect-and-slug-eating toads can be as simple as a sideways clay pot in a garden.

If you’re handy and want more insect control, consider building a multi-chamber bat house. Bird houses work best when designed for a specific species, such as bluebird, great grey owl, and wood ducks.

The National Wildlife Federation offers a one-stop checklist for anyone interested in doing more for local wildlife.

Project OptimistLisa McClintick

Project OptimistLisa McClintick

Who’s behind this column?

St. Cloud-based Lisa Meyers McClintick has been an award-winning journalist and photographer for more than 30 years. She’s also a teaching artist who is passionate about nature journals, and a volunteer Minnesota Master Naturalist. Follow her on Instagram.

This column was edited by Jen Zettel-Vandenhouten.