‘We pray upon them’: A Muslim take on end-of-life rituals

Few Somali Americans complete health care directives. Project Optimist spoke with an expert to learn some of the common questions Somali Americans have when they fill out the documents.

Few people in the Somali American community have health care directives – the documents that convey patients’ wishes to health care providers.

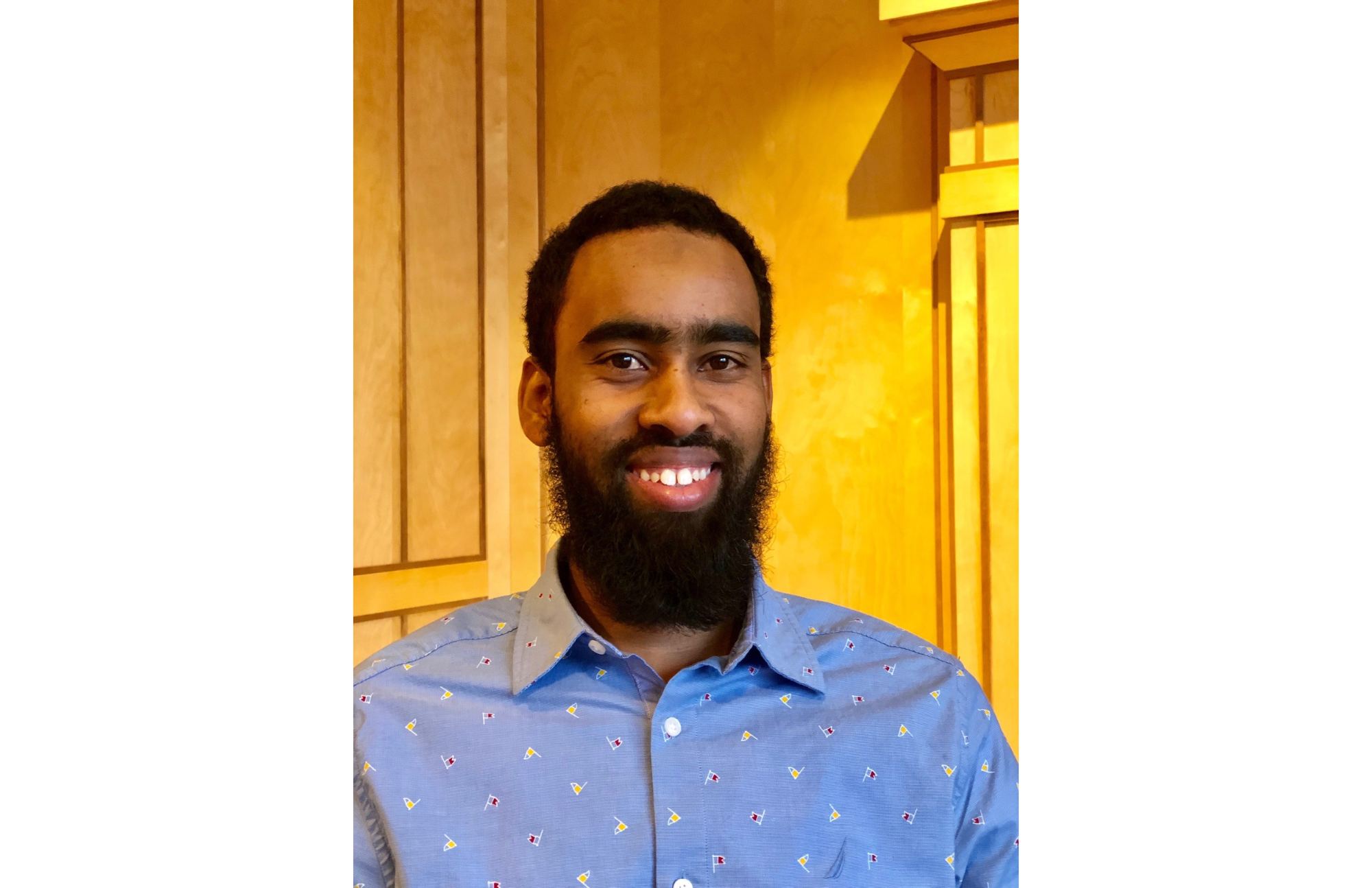

Trust is often a barrier for Somali Americans and immigrants when it comes to the health care system, including health care directives, said Abdalle Jamaa, spiritual care cultural liaison at CentraCare Health System.

But the documents are important to determine who will speak for people if they can’t speak for themselves, officials say. This recommendation stands even though templates for health care directives don’t generally align with the Muslim faith.

Three percent of Minnesotans identify as Muslim, up from 1% in 2014, according to the 2023-24 Religious Landscape Study conducted by the Pew Research Center.

People survived the civil war in Somalia, lived in refugee camps, and moved across the world to a new country with an unfamiliar culture, Jamaa said. Through those journeys, many were unfortunately taken advantage of and became scared it would happen again.

Community members also hear about negative experiences friends or family members had with the medical system and sometimes fear something similar will happen to them, Jamaa said.

“There's multiple layers of problems that happened in the past that led to where we're at today,” he said.

Start with a template, even if it’s not perfect

The nonprofit organization Honoring Choices has health care directive forms available in multiple languages, including Somali and Arabic. Honoring Choices is dedicated to helping adults in Minnesota with advance care planning.

However, Jamaa said he doesn’t think the Somali language paperwork aligns with the Muslim faith. He participated in a working group in recent years whose goal was to update the forms.

The forms have been translated but not otherwise changed.

The group met before current Executive Director Heather Thonvold joined Honoring Choices.

“What I was told by those who participated in the project is that a form specifically for the Somali community was not what the community ultimately decided they wanted,” Thonvold said in an email to Project Optimist. “Instead it was decided to translate the document into the Somali language but not revamp the document to make it different from the others.”

Despite Jamaa’s qualms about the advance care documents in Somali, he said people should still fill them out based on their faith.

“I think it's very important to engage in this conversation on a family level, in a time that we're not in crisis, we're not all emotional, and we're home,” he said.

There are short and long form advance care directives in Somali, and a short form in Arabic. The documents allow people to name health care agents and indicate their wishes about end-of-life care.

Align health care with faith practices

The Muslim faith teaches that Allah dictates when people die, Jamaa said, so Muslims should consider whether some medical interventions align with those beliefs.

Muslims also must say the shahada before they die, Jamaa said. The shahada is a declaration of faith.

“That is really important for a Muslim patient to say for their last word,” he said. “And so anything that can help the patient say that – whether it's calling for somebody that is Muslim, staff or family, or the community – to help them support their end of life spiritually in that way.”

Project OptimistJen Zettel-Vandenhouten

Project OptimistJen Zettel-Vandenhouten

How community cares for the deceased

Cremation is not allowed in Islam, Jamaa said, because Muslims believe the body feels pain in death as it did when the person was alive.

“Prophet Mohamed said, ‘Breaking the bones of a dead person is like breaking them when he is alive,’” Jamaa said. “So, cremation is seen as harmful to the body and wrong.”

A person’s family will contact a local mosque to begin preparations, as people are typically buried 24-48 hours after they die, Jamaa said.

Local funeral home staff will pick up the person’s body and take it to the funeral home. Once there, volunteers and family members will go to the funeral home to wash the body, Jamaa said.

“This washing is a ritual, and so there's a certain way to do it, and so the family, in collaboration with the local mosque, will do the washing,” he said.

The person’s body is then moved to the mosque, where community members come to pray.

"That's a religious duty, that every Muslim person should pray on them if they can,” he said. “So we pray upon them. And then that body will be taken to the graveyard and will be buried and honored in that way.”

Learn more

Jamaa can help CentraCare patients fill out their health care directives. They can also contact officials at their local mosque, he said.

This story was edited and fact-checked by Nora Hertel. It is part of Project Optimist’s series on End-of-Life planning. The series is supported by a grant from the Morgan Family Foundation. It is also part of Project Optimist's collaboration with St. Cloud Somali Community Radio which is supported by a grant from Press Forward Minnesota.

Project OptimistErica Dischino

Project OptimistErica Dischino