There's money in EV charging, but who can get in the market?

The mission to beef up charging infrastructure is more financial than technical, experts say.

Correction: This story was updated at 8:13 a.m. on May 29, 2025 to correct the actual cost to a Tesla driver vs. a Toyota Camry driver. To drive the range of the Tesla Model 3 (346 miles) would cost $3.75. A person who drives a Toyota Camry would spend $32.65 on gas to drive the same distance. Project Optimist regrets the error.

Many industries see charging infrastructure as a way to attract customers, as over over one-quarter of gas car drivers are interested in buying an electric vehicle and EV sales continue to rise.

For businesses to put more chargers on the road and remove a major hurdle to EV adoption, the challenge is more financial than technical.

“It's basically just finding sites, working with the funding set up, and just doing it. It's not rocket science anymore,” Jukka Kukkonen, founder of EV market and business consulting company Shift2Electric, said. “The technology is mature, and we can get it done.”

Sign up for Project Optimist's newsletter

Solution-focused news, local art, community conversations

It's free. No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Building to boost EV sales and home charging

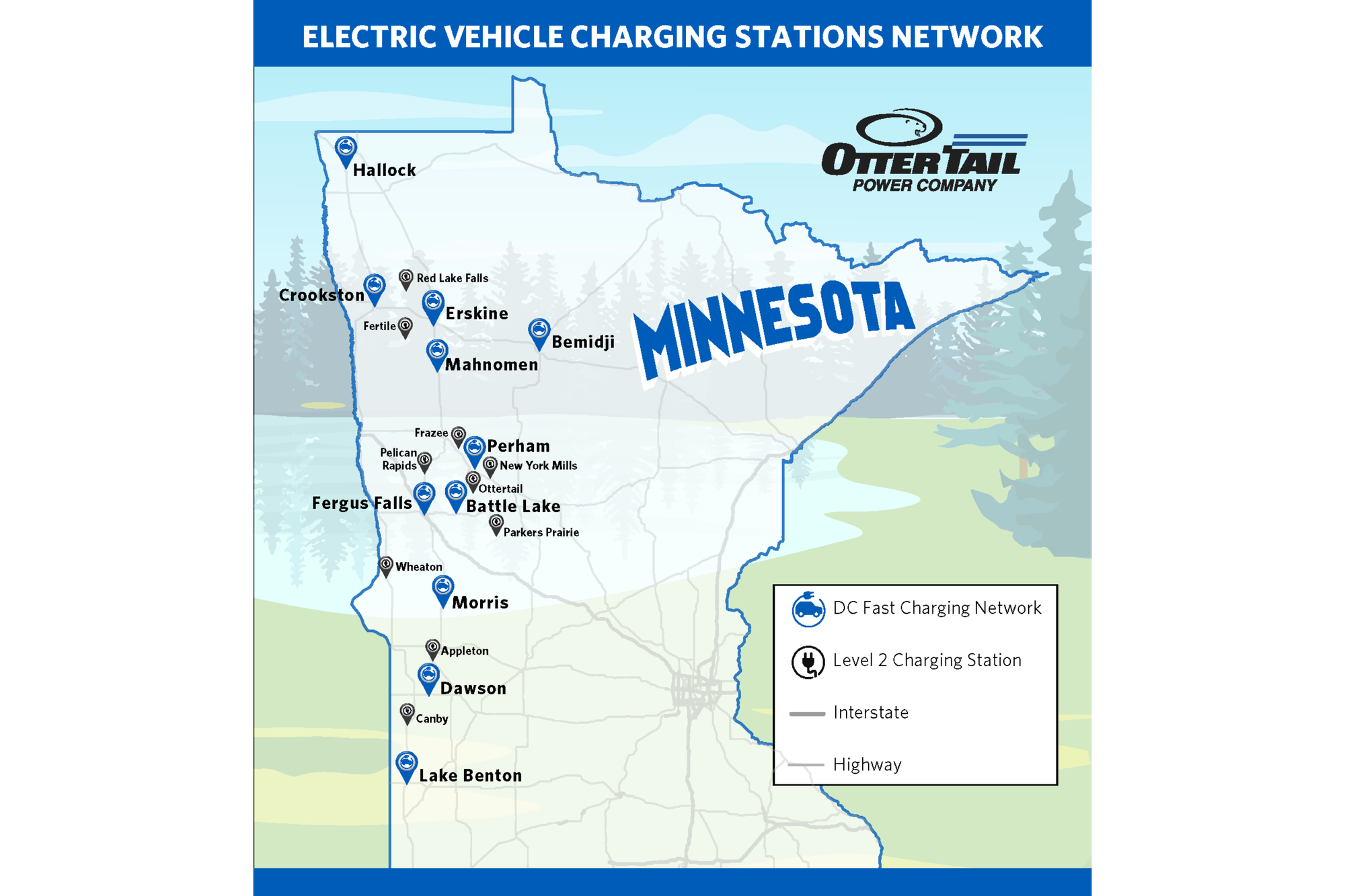

In 2020, Otter Tail Power Company saw gaps in charging coverage in western Minnesota. Rather than wait for third party investors, hesitant to take on investment risk in a region with low volume, utility officials decided to do it themselves and built a network of chargers from the state’s northern to southern border.

“As far as adding a lot more revenue, we don't see it as that. We see it more as we want to make sure customers don't get left behind,” said Jason Grenier, Otter Tail Power’s manager of retail energy solutions.

Grenier doesn't expect the utility to make back its investments in fast chargers directly. Such equipment costs at least $250,000 to install, he said.

The utility’s bet: range anxiety is eased, EV sales go up as a result, and Otter Tail Power makes money from at-home charging.

“Even if nobody uses them (the chargers), they at least know that they're there and they say, ‘Hey, electric vehicles will work for me, and I can charge at my house for 90-to-100-percent of the time,’” Grenier said. “There's going to be more revenue in (charging at) the house.”

Drivers save and businesses cash in

Utilities’ rates to charge one kilowatt hour are generally five cents or less, Grenier said.

A 2025 Tesla Model 3 has a 75 kWh battery. At five cents per kWh, a driver could travel the Tesla’s range of 346 miles for $3.75. At $3.02 per gallon of gas, a 2023 Toyota Camry, with a combined 32 mpg fuel efficiency, would cost a driver $32.65 to cover the same distance.

Jim Goodman, an EV driver who provides EV charging for guests at his North Shore cabins, said he saves about $200 a month on gas commuting to Duluth from Two Harbors and all the other driving his family does.

“My gas is super cheap at home and that's 99% of my miles. But [if] I got to make a big, long trip, I got to suck it up and get on a fast charger, and it's about the same [cost] as gas. You're happy to pay that because you got so much savings,” Goodman said.

With those savings, Kukkonen said more money stays in the local economy. Fuel is purchased from a local utility rather than oil companies, and less money spent on fuel means more money can be spent on goods.

A study in Nature Communications focused on California found that sales at points of interest within 100 meters of a charging station went up by 2.7% in 2019 and 3.2% between 2021 and 2023. Specifically for gas stations, BP Pulse CEO Sujay Sharma told Politico EV drivers stay longer and end up buying more in food and drinks.

Partners build networks

Even with a pivot to at-home charging, public charging will still be in demand. Urban areas will need charging locations for people who live in apartments that don't install chargers, ZEF Energy CEO Matthew Blackler said.

ZEF Energy’s main mission is to provide charging equipment, software, and maintenance services to local governments and small-to-medium sized utilities. The company also partners with electrical contractors and project developers to set up chargers for gas stations, workplaces, hotels, and other businesses.

In cases where potential sites need new transformers to power chargers, some utilities, like Otter Tail Power, build them.

Otter Tail Power typically gets a three-year minimum revenue guarantee from businesses to protect its customers from subsidizing those investments, Grenier said.

“If their revenue in the first three years covers the cost of that transformer, that's not an issue. Otherwise, we have to charge them some minimums each month to try to cover those facilities,” he said.

Project OptimistMair Allen

Project OptimistMair Allen

What a driver pays depends on a utility’s rates, which are approved by the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission. Who owns the charging site and infrastructure can also factor into consumer costs. The final tab for an EV driver to charge their vehicle may include costs of 5-15% if the site’s charging equipment is owned by a third-party company, Grenier estimated.

In its own five-year contracts with site hosts, Otter Tail Power gives businesses the option to own the station, Grenier said. But who will maintain the site for reliability is a concern.

“We want to make sure that if one of our chargers becomes [owned by a private vendor], that it is reliable,” Grenier said, “because if you lose that trust people will stop charging at your network.”

“In years to come, if we see that these vendors would be good partners in owning it, we would likely divest and hand them the keys to run those chargers,” he said.

Some businesses are starting to build their own networks. Walmart plans to establish its own charging network at thousands of locations by 2030, and IONNA, an enterprise of eight car manufacturers, is building gas station-like “rechargeries” around the country.

For businesses entering the charging arena, Blackler said foot traffic and the money to put equipment in the ground and maintain it will be key to success.

“I think we're now in that phase where things are getting real, you gotta start making money,” he said.

• How Stearns County addresses domestic violence

• Can community-led initiatives bridge Minnesota's Latino mental health gap?

• ¿Pueden las iniciativas comunitarias cerrar la brecha de salud mental para los latinos en Minnesota?

• How Extended Producer Responsibility will work in Minnesota

• Extended Producer Responsibility shifts recycling cost, promises investment

This story was edited and fact-checked by Jen Zettel-Vandenhouten.