How a grassroots group helps Minnesota youth touched by domestic violence

Rivers of Hope has worked to prevent domestic violence in Wright and Sherburne counties for 35 years.

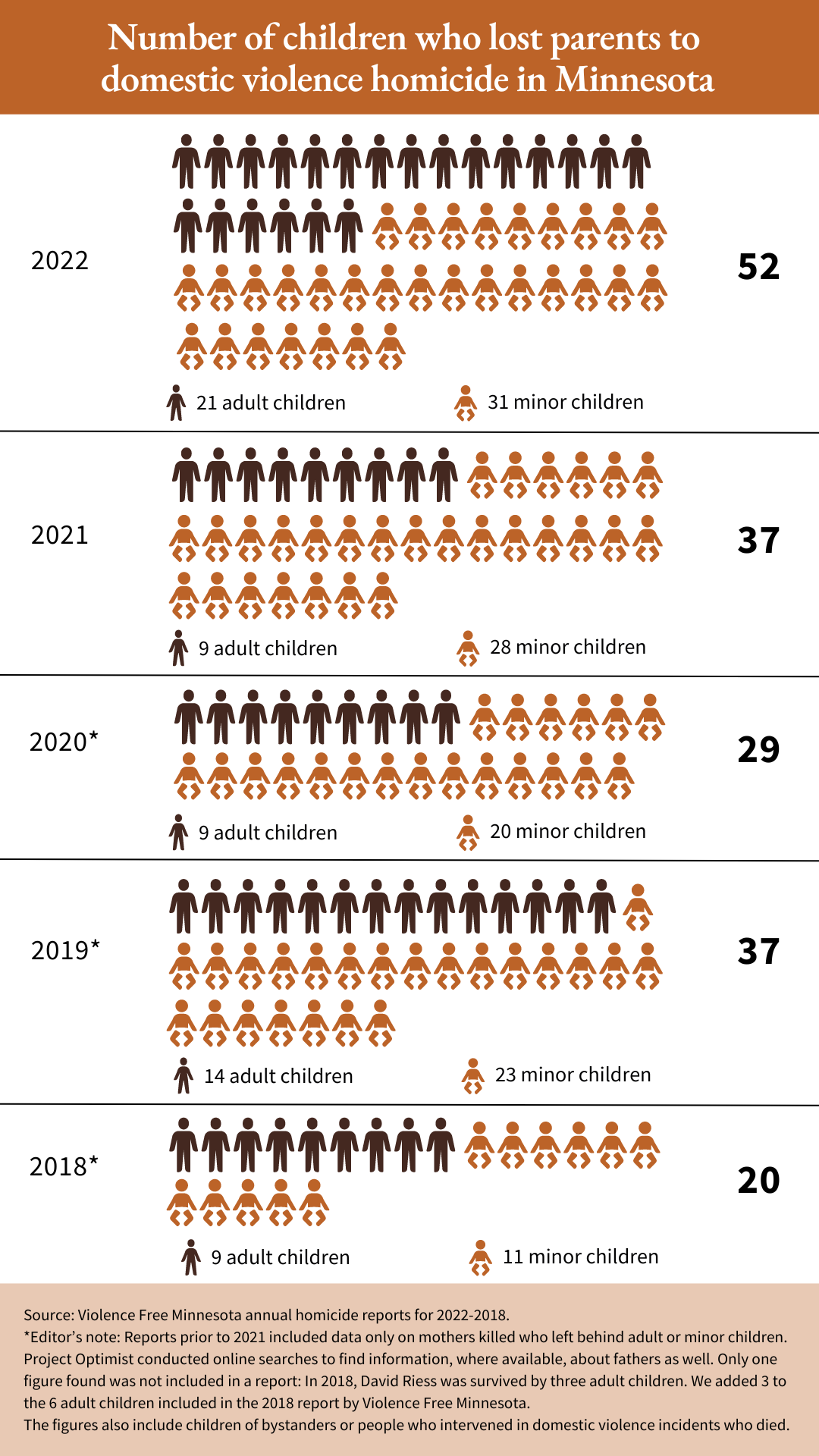

BUFFALO, Minn – At least 52 children lost parents to intimate partner violence in Minnesota in 2022, according to Violence Free Minnesota.

Thirty-one of those who lost parents were minors. Of those who lost parents, 31% witnessed their parent’s death or found their body.

The statewide domestic violence prevention organization compiles an annual Homicide Report, with 2022 being the most recent year with data available. The organization found that 24 people died as a result of domestic violence that year, parents of those 52 children, including three people considered bystanders or intervenors.

Children who experience violence, abuse, or neglect or who witness violence in their home are at risk of a host of issues as they grow up, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Toxic stress in particular can be a detriment that allows the cycle to repeat itself. "Children growing up with toxic stress may have difficulty forming healthy and stable relationships," reports the CDC.

But that's not the end of these children's stories.

Rivers of Hope, a central Minnesota nonprofit, has found it can help break cycles of violence and build resilience by providing children with counseling and help with basic needs.

The organization began its youth program in 1991, said Mel Harmon, outreach manager and youth advocate at Rivers of Hope. The nonprofit domestic violence prevention organization serves people in Sherburne and Wright counties free of charge.

Rivers of Hope offers educational lessons for middle and high school classes in both counties, as well as one-on-one meetings with students.

“Our goal really is to teach kids what healthy relationships look like and to empower them. They deserve that. They deserve those healthy relationships with parents, friends, and peers,” Harmon said.

Harmon’s dream is to start working with children on healthy relationship education in kindergarten and continue through 12th grade.

“A lot of the work we do, sadly, is reactionary,” she said. “I’m a big proponent of that prevention piece, so that by the time someone is 16 or 17 they understand what a healthy relationship looks like because we’ve started talking about it back in kindergarten.”

She would also like to create a mentorship program, where youth could be paired with an adult who can be another supportive figure in their lives.

Helping hand

Rivers of Hope serves 150-200 students annually through its youth program. In 2023, the organization's advocates conducted one-on-one sessions with 145 youth in Sherburne and Wright counties, Harmon said.

Brooke Oehser, a senior at St. Michael-Albertville High School, who has dual enrollment at Bethel University, was a victim of domestic violence for about seven years, along with her father and her siblings. She contacted police and connected with Rivers of Hope in 2020.

As a result, she lost relationships with some members of her extended family.

“Lots of people did not believe what happened and thought I was lying,” she wrote in an email to Project Optimist. “I also felt a ton of guilt for calling the police in the first place.”

To make it easier for her father to attend her siblings’ extracurricular activities, she stopped playing softball. She got a job when she turned 15 years old so that she could contribute financially, helping to pay for her own clothing and to cover spending money to hang out with friends.

When she found out about one-on-one sessions with Rivers of Hope, she was reluctant.

“I was very opposed to it at first, because I didn’t think that I needed any help,” Oehser said. “I thought I was going to let this time in my life go and move on from it, but then my first youth advocate … she was amazing and she opened her arms to all of us and she made sure that we were OK.”

How does Rivers of Hope's youth program work?

School staff, parents, mental health professionals, county workers, and others can refer children for individual sessions that take place during the school day. Most of the students are in middle and high school, although the organization will work with elementary students on a case-by-case basis, Harmon said.

The program is 100% voluntary. Rivers of Hope typically does one meeting with students to explain the program, answer any questions they have, and see if they are interested in meeting again.

Students who continue with Rivers of Hope decide how often they want to meet with an advocate – usually weekly, bi-weekly, or monthly. Once frequency is established, students will meet with the advocate for 20 to 30 minutes per session.

Typically, that includes safety planning and giving students coping strategies to manage the stressors in their lives.

“If they don’t feel safe at home, what can you do? We try to talk through those scenarios before they happen, so they can have clear thinking if something were to happen at home and they would know how to respond so that they’re safe,” Harmon said.

In addition to learning coping mechanisms and the differences between healthy and abusive relationships, Oehser said Rivers of Hope advocates offered gift cards to local grocery stores, as well as gas cards. Oehser also used the organization’s 24/7 crisis line – 763-295-3433.

“They will do anything they can to get you out of the situation that you’re in, and it’s all free, which is just amazing, because a lot of people who struggle with domestic abuse and teen violence aren’t able to afford counseling services,” Oehser said.

Oehser stopped seeing an advocate regularly in 2023, but someone from the organization reaches out to her every few months to check in and see if she needs anything.

She plans to attend college after graduation and is considering becoming a youth advocate.

“I’m trying to figure out if that’s what I’m going to do, because I’d like to help people like the people at Rivers of Hope do,” she said.

Measuring success

What does success look like? For Rivers of Hope, the answer is complicated.

“It is very difficult to quantitatively measure success in our youth program, especially when (students) don’t have the ability to leave their abusive home,” Harmon said.

However, the organization provides students with questionnaires at the beginning and the end of the school year.

For dating or difficult friendships, Harmon would like to see survey answers that indicate students feel they deserve respect, that they’ve ended the abusive relationship, and they are going to apply what they’ve learned about domestic violence in future relationships.

“For family violence, success can be measured as the student starts to recognize their value and worth and the fact that they do not deserve to go through what they are experiencing,” she said. “Ideally we want them to be able to recognize family violence so they make healthy decisions in their relationships as they move into adulthood.”

Sessions with individual students started organically, Harmon said, and as far as she knows, were not based on a particular model. Harmon did not know of any specific research outlining the impact of one-on-one sessions with youth affected by domestic abuse, dating violence, or toxic relationships.

However, she said the coping strategies and tools they give to youth are evidence-based. The program Rivers of Hope presents to classrooms on dating, Safe Dates, is evidence-based as well, she said.

‘Domestic violence does not discriminate’

While the youth program has been running for more than three decades, Harmon said there are a few obstacles Rivers of Hope regularly faces.

One is the belief among residents in Sherburne and Wright counties that domestic violence doesn’t happen.

“We like to think that all of our communities are safe. Domestic violence does not discriminate, and so it’s woven into all of our communities,” Harmon said.

Another challenge is funding.

The federal government cut $11 million from Minnesota’s Victim Crime Services allocation, which supports organizations like Rivers of Hope.

In 2023 the Minnesota Legislature approved spending $11 million over two years to cover the shortfall, as well as to provide additional grant funding. While the Legislature agreed to cover the shortfall, there’s no guarantee lawmakers will continue to fill the gap should it continue, said Hannah-Ruth Patterson, executive director of Rivers of Hope, in an email to Project Optimist.

“We still feel it (the federal funding shortfall) because we did not get the full amount we requested and have faced other funding challenges with decreased foundation grants, individual giving, etc.,” Patterson said. “Over the past six years Rivers of Hope has grown both in staff size and in reach, but we have not had any significant increase in Office of Justice Programs funding.”

It will cost the organization about $202,000 to run the youth program this school year, including two advocates and Harmon.

Larger systems in the community can also pose challenges. Harmon specifically cited the lack of affordable housing in Sherburne and Wright counties.

“There’s a lot of luxury apartments, there’s not a lot of low-income apartments and so when we have clients that are trying to leave their situation and we have nowhere to put them, their choice is often to stay,” she said.

Elements of the legal system can also be frustrating, such as when a court denies an order of protection Rivers of Hope believes is necessary, or when youth voices aren’t taken seriously, Harmon said.

In the room

Once a week in a small room at Wright Technical Center, students discuss some of the hard situations they’re living through with Harmon. Project Optimist observed one-on-one sessions held at Wright Tech on Jan. 9, and agreed to keep the names of the students and their situations confidential at the request of Rivers of Hope.

During each discussion, Harmon listens intently. She asks questions about activities the students are involved in, their families, and how they are doing. She makes eye contact throughout. While she brings case files and a notebook, Harmon does not consult the files or write anything down unless a student has a question she needs to follow up on.

The students may have witnessed or experienced domestic violence at home. Some might be navigating a difficult friendship or a toxic dating relationship. Whatever the situation, Harmon said Rivers of Hope advocates listen to each student’s experience and offer whatever help they can.

As each conversation winds down, Harmon asks a simple question: “What do you need from me?”

Kelsey Segerstrom, a school counselor at Wright Tech, said she has never had a student decline sessions with Rivers of Hope. She has been working with the nonprofit organization for four years.

Segerstrom sees myriad benefits from the program among her students, from increased attendance at school and better grades to more confidence in themselves. Sessions with advocates have helped students get out of toxic relationships, for example, she said.

“They’ve been super empowered,” she said. “They feel like they have a voice. They have someone that listens to them. They have someone that is not judgmental. They have someone that is always in their corner. I think it makes them feel like they have somebody that cares.”

Giving youth a voice in the metro

Listening to youth is also an important component of the work done at Tubman in Minneapolis, said Tamara Stark, senior director for housing and youth development. The nonprofit organization focuses on helping people from all walks of life overcome trauma, whether it be relationship violence, substance abuse, mental health, or another form of trauma.

Not all violence prevention organizations in Minnesota have programs focused on youth, Harmon and Stark said.

But there are numerous benefits to working with young people.

“They have so many ideas based on their experiences that they're trying to lift up for positive change. I think there's a general stereotype that youth are only bringing challenges … but yet the untold story is there's so much that they're also trying to make better and have ideas for,” Stark said.

Tubman’s youth programs, which include the school-based Voices in Prevention program, have benefitted from youth involvement over the past 30 years, Stark said.

Voices in Prevention's initial focus was teen dating violence, but feedback from participants helped staff add new components that students find relevant.

“Youth also have insights into what has gone on for adults they care about, grandparents they care about, the communities in general – they just have a really unique lens and are really on the pulse of things more than I think people give them credit,” Stark said.

Students have said they want more information about dealing with discrimination and navigating technology in their lives. They have pointed out the need survivors have for long-term housing and asked for a leadership program to spearhead change.

“I think that's critical for us to pay attention to (youth) because violence is learned in so many different ways,” Stark said. “And it also can be unlearned, and we want to be good community support to help make spaces where people of all ages can truly thrive.”