Drawn by Nature: Merlin app identifies unseen birds

Technology boosts appreciation for unseen singers, writes Lisa Meyers McClintick.

The sun rose by 5:30 am, looking molten through the veil of fog wisping off the Otter Tail River’s mirror-like surface.

A small group of people stood around the Chippewa picnic at Tamarac National Wildlife Refuge in Rochert, Minn., getting ready for a birding walk. They watched a blue-winged teal glide by, and I wondered out loud how you describe the sound of the intimate murmured sounds of assurance between trumpeter swans who are paired together. It’s almost like the last remnant wheeze of a child’s cardboard accordion as it’s discarded.

We have gathered around Don Kroodsma, a Michigan-born ornithologist, author, and retired biology professor who has biked across the United States recording bird songs and spent a lifetime studying what they have to say.

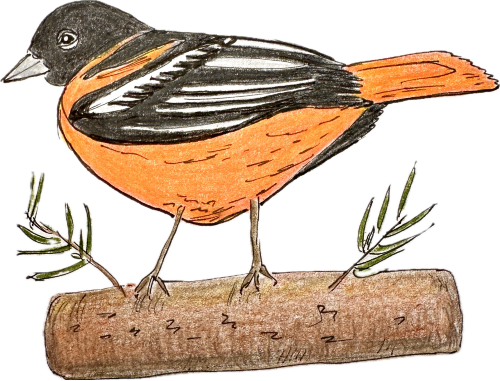

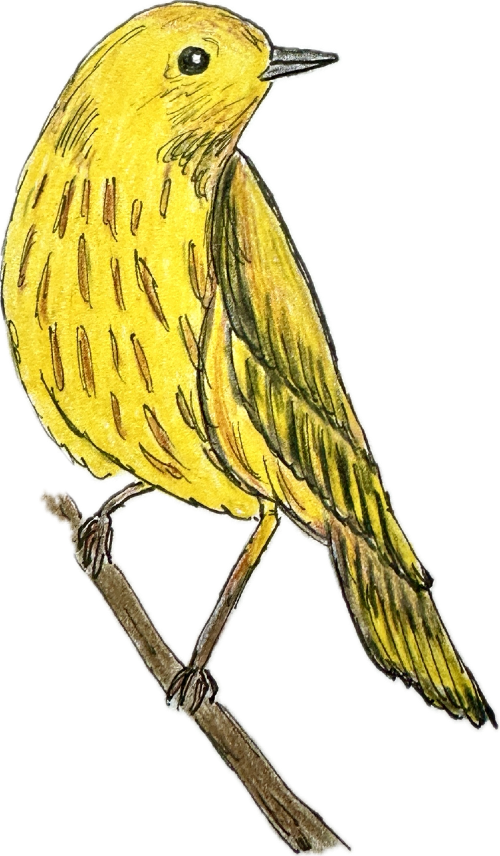

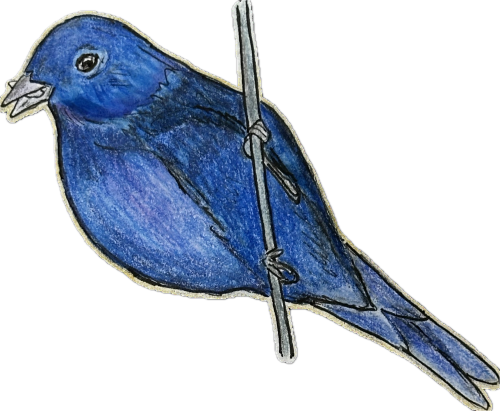

He doesn’t bring a camera into the woods. Or even binoculars, which most of the group carried. When he’s birding, it’s all by ear. He listened and held up a finger and cocked his head as he picked up the notes of a yellow warbler, a red-eyed vireo, or a blackpoll.

“There’s a lot of male-male showmanship in the morning,” Kroodsma said.

Most of the birdsongs we heard were either male birds trying to attract a mate, claim their turf, or protect its territory. Too bad the human equivalent of smack-talk isn’t as melodic.

Songs trigger memories

I’m a novice when it comes to bird songs. Like identifying birds visually, I’m usually the best with large, easy-to-see species. Pelican. Crane. Pheasant. Bald eagle. Egret. A few small birds I know well from growing up around them and seeing them at feeders.

Kroodsma, who was a keynote speaker at the 27th annual Detroit Lakes Festival of Birds in May, says bird songs can pull you back in time, tumbling through memories. He’s right.

All it takes is the trill of a red-winged blackbird, and I’m a kid again, growing up in the woods on the south side of the Twin Cities, watching red-winged blackbirds sway on the cattails of the wetland where I’d wait for the school bus.

Their calls and songs signaled spring as surely as the carpets of bloodroot, unfurling ferns, and false rue anemone that lured me down paths into the woods.

That 12 acres I knew so well were bulldozed and paved for suburban sprawl decades ago, and I’ve worried our kids and their dependence on electronic devices won’t have the same connection to nature. It turns out I need not have worried.

Those devices have managed not only to boost their interest in nature, but mine, too. We enjoy being able to quickly identify plants through identification apps, but what seems the most magical is the The Cornell Bird Lab’s Merlin Bird ID app, which launched its sound ID function in 2017.

Merlin app identifies unseen birds

Our 20-year-old will screenshot finds from her Merlin app, which can decode most of the sound it hears and tell you what bird is making that call or singing that song.

“I feel like I have X-ray vision!” I’ve told others. Seriously, being able to identify the birds we can’t see based on the songs we hear, is like stripping away all the leaves and being able to see who’s making the sounds.

While I’ve never been stellar at spotting tiny warblers and songbirds flitting through the trees, knowing what I’m looking for (based on what species is doing the singing) helps immensely. I can watch for the right color of feathers or the right habitat if a bird likes the treetops, the shrubs, or being near water.

If multiple birds are singing, the Merlin app will show photos of them all and highlight each species as it chimes into the woodland or prairie chorus. It also shows a spectrograph, which is a visual map of the sounds a bird is making.

According to a press release from Cornell, the app had been installed 15 million times as of November 2023 and included more than 55,000 photos and 26,000 recordings in its database.

Tuning into nature’s daily chorus

Thanks to what I’ve learned from using Merlin, I’m paying more attention to what I hear—even if it's a bird song I might hear in a parking lot. A quick use of the app by Brainerd’s Central Lakes College June 3 showed a rainbow of eight birds singing in only a 90-second recording, which included a scarlet tanager, American goldfinch, and a house finch.

In early May, I had stopped along the Sherburne National Wildlife Refuge’s wildlife drive after hearing a complicated birdsong and seeing a flash of reddish brown in the treetops.

It was the first time I saw (or even knew about) a brown thrasher, also called a fox-colored thrush. It turns out, according to Kroodsma, this plain-looking bird with yellow eyes and a curved bill is one of the showiest and most accomplished singers. It can sing more than 1,000 songs.

Thrushes, sparrows, and songbirds such as warblers tend to be the most-admired singers, often learning songs from their elders. If birds’ vocal gymnastics ever seem confoundingly complex, consider it their masterful use of their syrinx, an organ where their trachea splits into two bronchial tubes. It’s the equivalent of using two voice boxes at once. Some birds can mimic two birdsongs simultaneously, using one side of the syrinx for each one.

Knowing all this elevates a simple evening walk or sitting in the backyard. What used to be background sounds now feels like a conversation among birds I can now recognize by ear. And if we’re lucky, it’s more than one song. It’s a neighborhood concert.

As Kroodsma told the group of birders in May, “Go listen like you’ve never listened before. There’s so much you can hear.”

Who's behind this column?

St. Cloud-based Lisa Meyers McClintick has been an award-winning journalist and photographer for more than 30 years.

The second edition of Lisa’s "Day Trips from the Twin Cities" hit bookshelves June 4. When she’s not writing, she’s in the woods taking photos, working on her nature journal and volunteering with the Minnesota Master Naturalist program.